As tools such as Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar have

become more widely accessible, it has become much easier to create

metrics at the article level. This overcomes some of the major issues in

using journal-level metrics to evaluate authors? work. Instead of

evaluating work based on the company it keeps in a journal, it is

possible to evaluate the individual articles and furthermore aggregate

these measures to the author level and above (research groups,

institutions, funders, countries, etc.).

Author-level bibliometrics

Since the dawn of modern science, the simplest metric at the authorlevel has been the number of papers published. Along with all

author-level metrics it is complicated by multiple authorships:

- Should only the first author be counted?

- Should credit be split equally between authors?

- Should a paper be counted once for each author listed?

- What if there are 1000 authors on the papers?

allocate each author a count for each paper on which they are listed as

an author, regardless of position on the author list or number of

co-authors.

The other simple metric to calculate is total citations, which simply

refers to the number of citations received by an author?s published

work. These metrics either reward prolific authors or authors whose work

has been very highly cited. As a compromise, various other metrics such

as average (mean) citations per article can be used. However, as

citation distributions are highly skewed this measure is not

satisfactory. Instead, a median citation per article could be used, but

this can be reduced by a long tail of uncited or poorly cited articles.

Therefore a new metric was created.

The H-Index

The H-Index was defined by the physicist Hirsch in a 2005 paper in the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences. The H-Index is a relatively simply metric defined as:?A scientist has index h if h of his/her Np papers have at least h citations each, and the other (Np ? h) papers have no more than h citations each.?

Therefore to have an H-Index of 10 you must have published at least

10 papers that have each been cited 10 times or more. This has an

advantage that is not skewed upwards by a small number of highly cited

papers like mean citation per article count would be but also not skewed

downwards by a long tail of poorly cited work. Instead it rewards

researchers whose work is consistently well cited, although a handful of

well-placed citations can have a major effect.

Issues with the H-Index

Although the basic calculation of the H-Index has been defined, itcan still be calculated on various different databases or time-frames,

giving different results. Normally, the larger the database, the higher

the H-Index calculated from it. Therefore an H-Index taken from Google

Scholar will nearly always be higher than one from Web of Science,

Scopus, or PubMed.

As the H-Index can be applied to any population of articles, to

illustrate this I have calculated H-Indices or articles published since

2010 in the journal Health Psychology Review from three different sources:

- Google Scholar: 19

- Web of Science: 13

- Scopus: 12

Like all citations metrics, the H-Index varies widely by field and a

mediocre H-Index in the life sciences will be much higher than a very

good H-Index in the social sciences. But because H-Indices have rarely

been calculated systematically for large populations of researchers

using the same methodology they cannot be benchmarked. The H-Index is

also open to abuse via self-citations (although some self-citation is

normal and legitimate, authors can strategically cite their own work to

improve their own H-Index).

Alphabet soup

Since the H-Index was defined in 2005 numerous variants have beencreated, mostly making small changes to the calculation, such as the

G-Index:

?Given a set of articles ranked in

decreasing order of the number of citations that they received, the

g-index is the largest number such that the top g articles received

(together) at least g2 citations.?

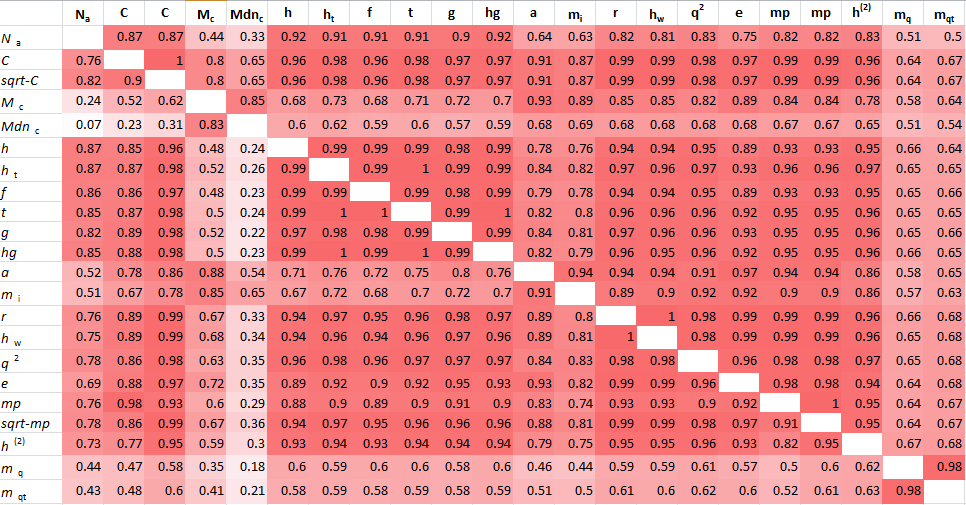

However, a paper published in Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives found that if you take the correlation of author rank by the various metrics they are all very highly related.

Source:

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15366367.2012.711147 Notes:

Values on the diagonal (1.00) are omitted, values below the diagonal are

the usual Pearson product-moment correlations, and values above the

diagonal are Spearman rank-order correlations. Because values are

rounded to two decimal places, an entry of 1.00 does not necessarily

indicate perfect correlation.

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15366367.2012.711147 Notes:

Values on the diagonal (1.00) are omitted, values below the diagonal are

the usual Pearson product-moment correlations, and values above the

diagonal are Spearman rank-order correlations. Because values are

rounded to two decimal places, an entry of 1.00 does not necessarily

indicate perfect correlation.

Issues with citation metrics

All of the author-level metrics based on citations have issues related to the inherent nature of citations.- Citations can only ever go up.

- Positive and negative citations are counted the same.

- Citations rates are depend on subject.

- Different research types have different citation profiles.

- Only work included in the databases is counted.

history including review articles cannot be compared with a

post-doctoral researcher in the life sciences nor with a senior

researcher from another field.

Further, researchers who have published several review articles will

normally have much higher citation counts than other researchers.

Publishing books or giving conference papers which are not included in

the Web of Science or Scopus to the same degree as journals means that

some work is not counted when using these tools.

Conclusion

Although tools such as ORCID, Researcher ID, etc. are starting tohelp with disambiguating authors, the most common name in Scopus has

more than 1,800 2013 articles associated with it. Though most authors

can calculate their own author metrics easily, it requires a totally

accurate publication list to create author-level metrics on a systematic

basis as groups of researchers and ambiguous author names still cause

an issue here.

Unlike journal-level citation metrics that mostly come from defined

providers, author-level metrics are undefined in terms of time-frame,

database, and type of research to be included. At the extreme end

multiple authorships can cause problems, with so many authors sharing an

equal amount of credit for single paper.

In reaction to some of these issues there has been a push by some in

the science communication community to look beyond citations and usage.

The growing and rapidly changing field of altmetrics will be covered in a

future post.

Print This Post

Print This Post